Zoë Wells

Finishing Zorrie and finding out, through his acknowledgements section, that Laird Hunt kept a copy of Virginia Woolf’s The Waves on hand throughout the writing process is the least surprising part of a novel that, generally, does not try very hard to surprise you. Zorrie is a gentle book, or at least is trying to be. It follows the life of its titular character, from young orphan through to attempted pregnancies, from wide-eyed, young adult, to stay-at-home wife, to widower.

It’s a polarising book in the same way that Woolf’s own work is. Some will enjoy the gentleness and the general lack of plot. Some will find this verging a little more on the dull end of the spectrum. I’ve often found that Woolf, eventually, usually after a lot of rumination, sits well with me, so perhaps it is surprising to hear the undertone of negativity in this review of Hunt’s own work.

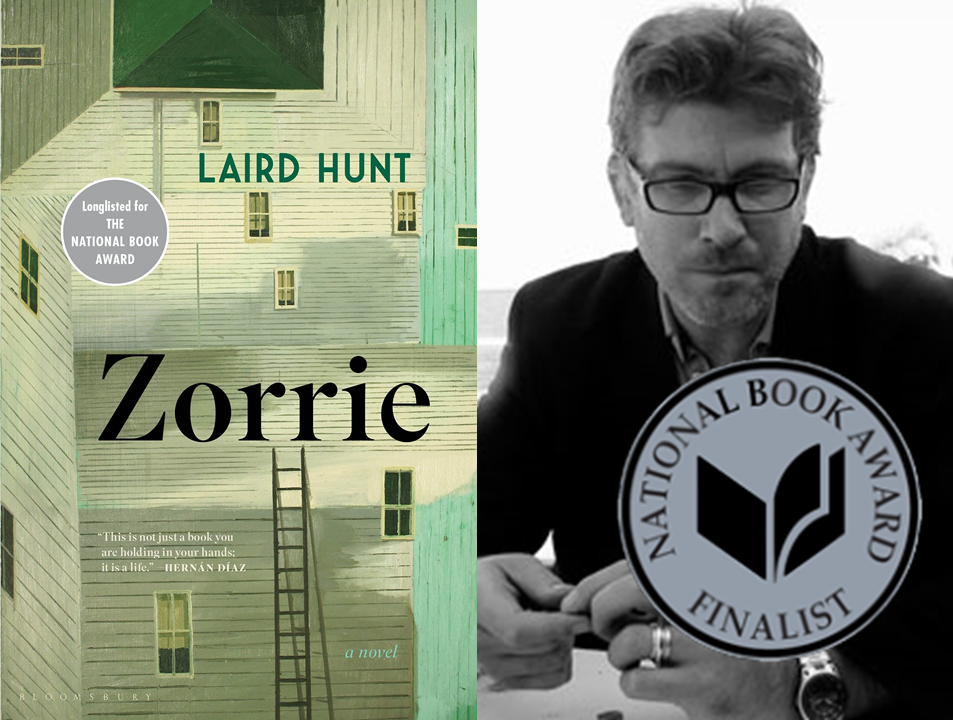

The novel opens on Zorrie, a girl who is forced to live with her aunt at a young age due to tragic circumstances. The plot is punctuated by her various moves in life, as she travels around and tries to find a place where she might fit in. Each of these areas is presented as a little vignette, with it’s own cast of characters and quirks, which will gradually move aside to present a new scene. Alyson Hagy’s New York Times review of the novel called it a portrait of “America itself”: it is slow and unsure of its place, constantly trying to fit in to some preconceived idea of what it should be. Zorrie is author Laird Hunt’s seventh novel and is published with Bloomsbury.

“[Zorrie] asked Janie what it was like to have a mother, and Janie leaned over and gave Zorrie a kiss on top of her head and then turned her around and gave her a quick kick in her seat and told her that having a mother was those two things, and that if sometimes it was more one than the other, it all balanced out in the end.”

The difference between Hunt’s work and the copy of Woolf’s The Waves that sat on his desk throughout writing is, as I see it, one of pacing and narration. Woolf mastered the art of the narrative eye – you need only look at any article written on Mrs Dalloway to know this. Her work is taught across literary programs and writing courses all over the world for this very reason. I don’t doubt that Hunt himself, a professor at Brown, has taught Woolf countless times for this very reason. In Woolf’s hands, we are deftly carried through changing narrative voices; through gentle stories that move slowly slowly slowly, and then all at once accelerate, but the whole while her speechlike style of writing is carefully supporting us.

This is what feels oddly absent in Hunt’s work. Zorrie makes for an objectively interesting narrator: she has a colourful and often tragic life, one that should be quite interesting to follow. From the introduction of her work painting watches in radioactive radium, we know full well, as modern readers, what this means – the perfect Chekhov’s gun. The character of Noah, who is cloaked in mystery and whose wife is completely absent, having been sent to a sanatorium, is well handled too. But the narration style is a little too lackluster and distant to carry readers – or at least this reader – through the lulls in plot. Rarely does Hunt allows us to see into Zorrie’s own emotions, and when he does, it’s all too often in the moments where we don’t really need to be told her thoughts in such explicit terms. We know that a widower feels sad – is this really the right moment to be brought into the inner workings of the character’s mind?

That being said, Zorrie is, on a sentence level, a truly lovely novel at times. Sections like:

“The crops went in, the crops were cared for, the crops came out. The earth rested in its right season, and she with it. If the ache of Harold’s absence descended on her during the quiet months, she would take a rag to it with her mind and rub.”

How wonderful. And it’s in moments like this when I want to forgive Zorrie, or read it over another time, because there is most certainly a great writer working behind the novel. But something, for my part, has been lost in the woods. Perhaps, then, it should be appreciated as a work of poetry: something beautiful with something to say about the world, even if, when read a little too quickly or in larger bites, it drags a tad.

The choice to somewhat emulate Woolf’s style should be appreciated, at the very least, for the fact that it is a deliberate one. Hunt has not written this book without style: he has simply picked a style that is polarising, doing so in full knowledge of this, and that in itself can be respected. Other reviewers have rightfully praised the book for its strong voice and interesting narrative. These are things that should be praised: we would not want every book to read the same. But in this case, and in this reviewer’s opinion, Zorrie comes across less as an advancement of a genre and stylistic tradition, and more of a pale shadow of what it could have been.

This piece is part of a series of reviews of the National Book Awards 2021 Fiction Shortlist. The shortlisted texts are: Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr; Hell of a Book by Jason Mott; Matrix by Lauren Groff; The Prophets by Robert Jones Jr; Zorrie by Laird Hunt.

About the Contributor

Zoë Wells (she/her) is a Swiss-British writer and poet based in the UK. She is currently studying towards an MA in Creative Writing at the University of Manchester, having previously received her BA in English Literature and Creative Writing from Warwick. She is working on a debut historical fiction novel, alongside a poetry pamphlet, and has had her short fiction and nonfiction published in a number of magazines. Find her on twitter at @zwells_writes or visit her website.

Leave a Reply